The Philippine Connection

Here are some dots. Opium, Morphine, Fentanyl, China, America, the Philippines, Germany, Hitler, Narcos, Rizal, Teddy Roosevelt Trump, and our very own President Duterte. We’re going to connect them in a quick exercise in surprising connections in the War on Drugs.

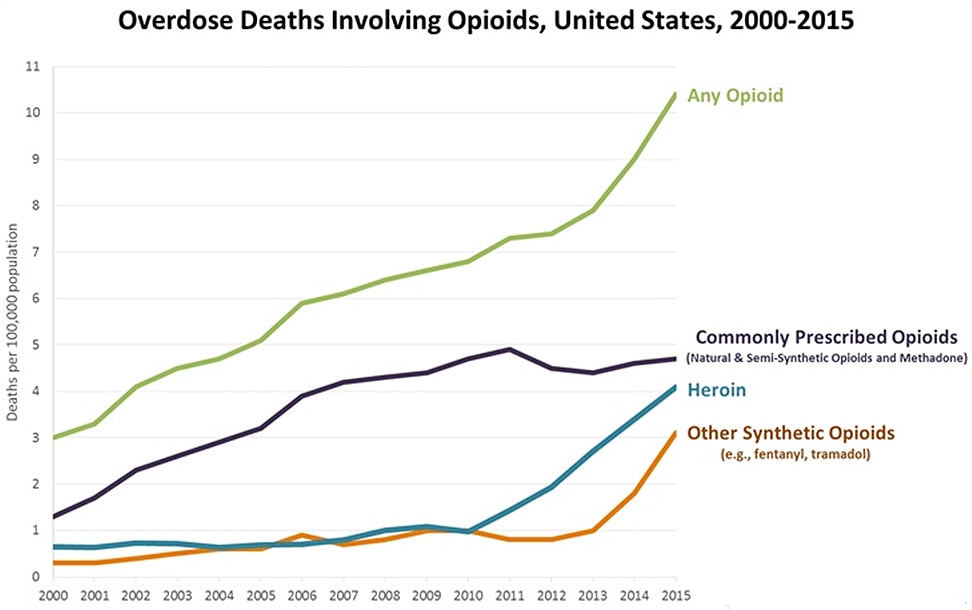

A few days ago, US President Donald Trump proclaimed a medical emergency, because of the ongoing Opioid epidemic in the United States. As this chart shows, Now a quick definition. There are opiates, which are painkillers made from the Opium poppy, and there are opioids, which are chemical substitutes for opium-derived products, also meant to be painkillers and, in some cases, much more powerful.

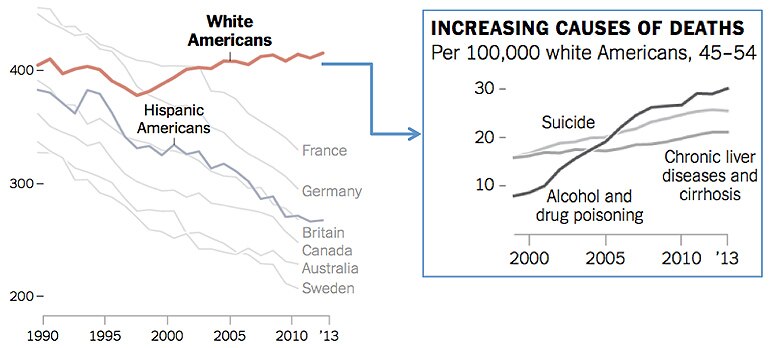

While opioid abuse is going down in places like Europe, it’s spiking in America, particularly among white people. Along the way, when doctors aren’t prescribing drugs like Fentanyl, addicted individuals are looking for heroin on the streets as a cheaper alternative.

Speaking of Fentanyl, because of the chronic pain he endures because of some chronic diseases he has, our very own President has pointed out he had to resort to Fentanyl in the past to the extent his doctors got worried. That’s the point as far as he’s concerned. He has medical supervision. As for other drugs, he himself believes as we all know, that there is a dangerous intersection between criminals distributing drugs, and politicians on the take from drug dealers. Hence, our home-grown War on Drugs which he took the time to explain to his favorite author, Ioan Grillo, whom we’ve covered before.

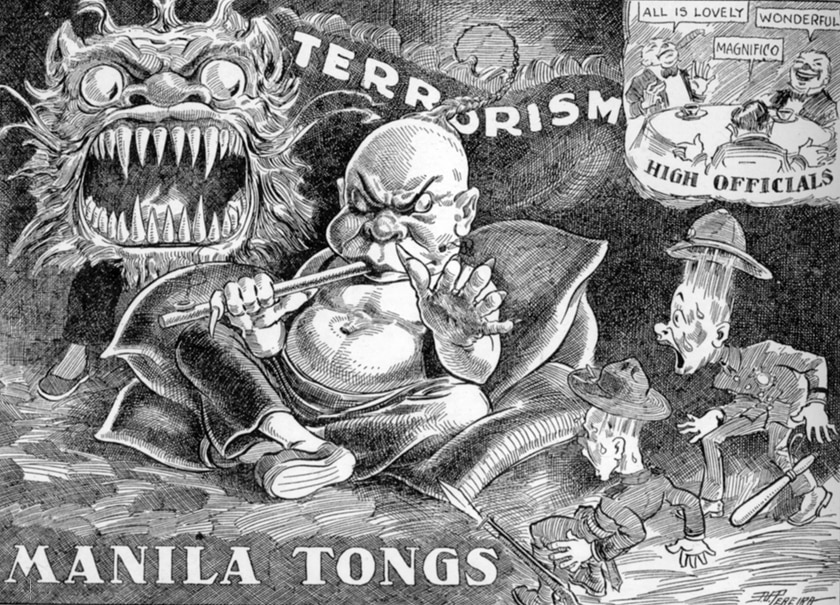

Now, here’s where we start laying out the dots and connecting them. This Free Press editorial cartoon from the 1920s. It could be published today and still be relevant. There’s a Chinese opium dealer. There are supposedly helpless policemen. There are high officials turning a blind eye to the problem.

Even before the Flower-power 1960s with its Jimmy Hendrix and marijuana, drugs were known here. As Ambeth Ocampo once pointed out in a column, even Rizal, writing to a fellow scholar, said he’d tried hashish, a sticky, concentrated derivative of marijuana. He said it had been strictly for scientific purposes. He also pointed out that opium was known in the Philippines.

Now, as we proceed from our first dots, we’re going to rely on two books, El Narcoby Ioan Grillo, about the rise of the Mexican drug cartels which started with the distribution of Opium and marijuana at the turn of the 20th Century, and Blitzed: Drugs in Nazi Germany, by Norman Ohler, about how the Nazis and Hitler got hooked on artificial stimulants and sedatives during the Third Reich.

Let’s start with Ioan Grillo’s book, which gives a fascinating background to why the Chinese were so instrumental in the growth of the drug trade in opiates and later got involved, too, in the trade in opioids.

Opium from the opium poppy has been known since the most ancient times, and for millennia it was the only source of narcotics. The poppy produces a sap which is can be gathered and concentrated to make opium which can be smoked.

The British in the mid 1800s started importing opium from their colonies bordering on Afghanistan to China, and the Chinese government tried to ban it. Britain went to war to force China to allow their sale of drugs, taking over Hong Kong and other places, inflicting a humiliation still powerfully felt in China to this day.

Chinese workers and settlers all over the world, whether to the Philippines or to Mexico, would set up opium dens and mastered the business of bribing officials. In Mexico and America, Grillo says, Chinese laborers brought in to build railroads brought with them not only the opium habit, but poppy seeds, which is how Mexico started growing opium.

By the turn of the 20th Century, Teddy Roosevelt, the US President who, as Vice President, had schemed to send the US Navy to Manila in 1898 and have America conquer our country, had gotten so alarmed by the spread of opium that he lobbied for international gatherings and treaties to limit the opium trade. American missionaries in the Philippines went back to the United States with horror stories of Chinese opium dens, and Americans began to discover there were opium dens in San Francisco and other places, too.

The alarm over opium which also had racist elements to it—the fear of drug-crazed Chinese taking advantage of drug-dazed American women was a particularly horrifying thought to white Americans—soon included other drugs, such as cocaine which as we all know had gotten so popular even soft drinks included it. And here comes another dot: a gentleman named Francis Burton Harrison, who later became Governor-General of the Philippines, adviser to three Philippine presidents, and a Filipino citizen who chose to be buried in Manila. As a congressman, he sponsored the Harrison Narcotics Act, the first laws aimed at suppressing the spread of illegal drugs –in fact it’s the law that made marijuana, opium and cocaine illegal in the first place.

Which now brings us to our next dots, far from Manila and Washington in the 1910s, and on to Berlin in the 1920s. Norman Ohler, in his book, says the Nazis, like so many authoritarian populist movements, found a War on Drugs to be very popular and very convenient. The Nazis promised a crackdown on opium and cocaine.

Pain killers had gotten a big boost among the Germans and indeed all armies that fought in World War I, because so many wounded, meant doctors needed a way to keep soldiers pain-free and calm as they waited to either die or undergo surgery. The use and abuse of painkillers like Morphine led to thousands of addictions, fueling demand and crimes among veterans in the 1920s.

Hitler, campaigning for, and after achieving, power, blamed the Jews and other groups for the criminal underground peddling drugs to what he said were innocent Aryans. Hitler’s anti-drugs campaign was focused not on curing addiction, but eliminating places like music halls and cabarets where people made fun of the powerful, and cracking down on practically anyone who could be accused of favoring drugs and were therefore, anti-German.

Never mind that there remained high-profile addicts like Hermann Goering, Hitler’s air force chief and designated successor, who had gotten addicted to morphine when he was wounded in Hitler’s attempt to grab power in Munich in the 1920s. But Goering, for one, was addicted to an opiate—morphine is derived from opium. Something else was happening in Germany in the 20s and 30s: the invention of something unrelated to pain killers. This was what we now know as speed.

The German genius for chemistry gave us things like Aspirin but also, what is more technically known as methamphetamines, chemicals that rev up the system, meaning you can go without sleep for days, you lose appetite, and feel like superman. In the 1920s the first such amphetamine, known as Pervitin, was marketed. It proclaimed you would be energized for work and lose weight in the process. It sold like crazy. It was even mixed into chocolates for housewives to stimulate them to do more housework.

When Hitler went to war against Poland, the fast pace of the German way of waging war meant ways had to be found to keep soldiers on the move and awake. Eventually, a so-called Stimulants Decree was issued, which ordered German soldiers to receive doses of amphetamines. In contrast, French soldiers were getting a liter of wine a day while German soldiers got stimulant pills. So, the Germans kept winning and as time went on, a side effect of amphetamines—aggression, for example—meant it became easy to dose soldiers with drugs so they could more easily round up Jews and shoot them.

Even Hitler got addicted. His doctor, Theodore Morrel, mastered what addicts call a speedball: a combination of uppers and downers. So, Hitler functioned for the last two years of his life on a cocktail of cocaine, amphetamines, and sedatives. His generals, not knowing he was on drugs, thought he was glowing with a supernatural brilliance as he would speak for hours in meetings, going from one random topic to another, shouting and cursing at the world. Then Hitler’s doctor ran out of drugs, Hitler crashed, got depressed, and shot himself.

The Allies soon discovered this German secret and started dosing their own troops with both uppers and downers. American and British versions of amphetamines were issued to troops. Wounded troops were dosed on morphine, as you know from watching Band of Brothers, where syrettes were issued to medics to inject into wounded troops. So it was in Korea and in Vietnam—with generations of troops introduced to drugs.

It was the hangover from wartime—dosing people in pain on the battlefield became dosing people in pain in civilian life—that fueled the rise of the drug culture, and the waves of changes since, as doctors and drug dealers keep finding new waves to satisfy public cravings. And among these dots, you now see, the surprising place the Philippines has played in this global tragedy. So, if you have something left over from your end of the month pay, why not spend some of it in a bookstore, and get Grillo’s and Ohler’s books? You definitely won’t regret it.