Unhealthy rumors

In eleven days, it will be one year since Rodrigo Duterte became president of the Philippines. When he took his oath in 2016, it marked seventy years since the country last had a president of Cebuano ethnicity. To put our president’s age in context: he was a Liberation baby, one year old when Sergio Osmeña became president, and in turn, he became president seven decades after Osmeña left office.

In fact when President Duterte became president at the age of 71, he became the oldest person to assume office. Of our three oldest presidents, Sergio Osmeña, was 66 when he became president in 1944, and 68 when he left office in 1946.

Ferdinand Marcos, who had started out as one of our youngest president, was 69 years old when he was removed from office in 1986.

And Fidel V. Ramos, who’d been the next-oldest to Osmeña, was 64 when he became president in 1992 and 70 when his term ended in 1998.

But age, in and of itself, is no guarantee either of ill-health or a short presidency. Osmeña himself was only a month younger than his predecessor, Manuel Quezon, but succeeded to the presidency.

In fact, the very existence of the vice-presidency as an institution owed a lot to everyone expecting Quezon, who had tuberculosis, would become president, and therefore there was the need for a designated successor just in case –with everyone assuming, too, that Osmeña would be that man.

However, by 1946, white-haired and hard of hearing, Osmeña suffered in comparison to what people considered his younger, more vigorous rival, Manuel Roxas.

Osmeña ended up having the last laugh. He outlived Roxas, who died in office in 1948, by 13 years.

When Roxas died of a heart attack, the second constitutional succession in our history took place. The problem was, when Roxas died, Quirino had been at sea, recovering from a heart attack.

He would continue to have heart trouble during his presidency, spending most of his reelection campaign in 1953 in a hospital room.

So, not only did Osmeña outlive Roxas, he outlived Roxas’ own successor, Quirino, who died in 1956, by 4 years. And he even outlived Ramon Magsaysay, who became our youngest elected president in 1953, by 3 years: Magsaysay died in a plane crash at the age of 50 in 1957.

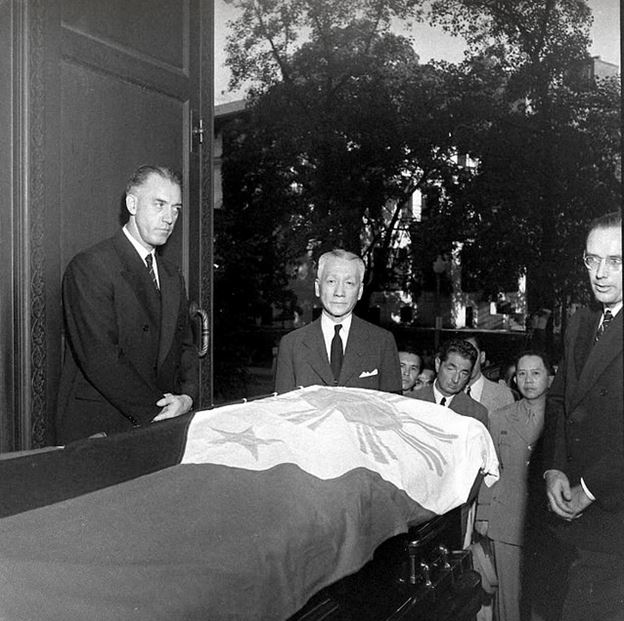

This meant that aside from Emilio Aguinaldo, seen at the right, Osmeña, on the left, outlived three of his successors. Aguinaldo outlived five of his successors.

This only goes to prove two things. As a government and a people, we have lots of experience handling ailing presidents and situations when they die in office. But we owe our current rules on what to do when presidents are sick, to one president.

That president is our current president’s idol, Ferdinand E. Marcos. By the late 1970s, the formerly vigorous dictator had begun to have health problems, and as the years wore on, they increased.

If you thought the rumor mill was in overdrive over the five days President Duterte was out of the public eye, ask the older generation what sort of rumors swept the country about Marcos.

In 1986, during the snap election campaign, the focus became the obvious ill-health of the great dictator, something that couldn’t be hidden from the public.

From photos where people saw his bandaged hand, to reporters snooping on everything down to what was in the toilets during the president’s campaign pit stops, health became an issue.

When the time came for a new constitution, the framers of our 1987 Charter had Marcos in mind when they put in this provision. It’s in the article on the Executive Branch:

Section 12. In case of serious illness of the President, the public shall be informed of the state of his health. The members of the Cabinet in charge of national security and foreign relations and the Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines, shall not be denied access to the President during such illness.

So what does this tell us? Well, first of all, it tells us that Rep. Gary Alejano’s wrong when he said being informed about the president’s health is a matter of national security. It’s not. It’s about the public’s right to information about the president’s health.

And here, we have lots of examples about how it’s supposed to go.

Former President Ramos had everything from surgery to a chipped tooth and it was all revealed to the public together with regular updates, including then-Vice President Estrada being informed.

Former President Arroyo, during her times of being under the weather, also had her procedures and health status detailed to the public.

You might even remember that when former President Aquino had a cold or the flu, the media was informed, and he himself told the public in his last State of the Nation Address, that he had dispensed with marching down the aisle of Congress because he wasn’t feeling well.

For his part, as he approaches his first year in office, it’s fair to say President Duterte has been forthcoming about his health, even during the campaign. He himself revealed he has various ailments, ranging from Barret’s esophagus, Buerger’s disease, to migraines and dizziness, leading to the past use of the pain reliever Fentanyl and, most recently, using an oxygen concentrator machine to help him sleep at night. Chronic ailments, maybe, but not life-threatening.

Over the weekend, he reappeared and told everyone he’d been tired, and even took a secret trip. Perhaps in his second State of the Nation Address, he might even say what that trip was about and where he went.

As is the privilege of his office, he has the last word: I’m not worried about my health, he said, because after all we have a Vice-President. And as history shows in the case of our other Cebuano president, it might just be Rodrigo Duterte will have the last laugh, too.